|

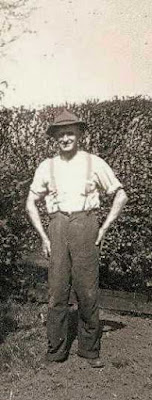

| John as a young man |

John lived nearly all his life with his mother, my great grandmother, in a house – now gone – in the Fishwick area of Preston. Shortly after his mother, Jane, died, well into her 90s, and John himself was retiring age he moved, in the mid 1950s, to a little wooden bungalow that he had bought some years before on the A6 at Cabus near Garstang, about 10 miles north of Preston. The house in Preston where he lived for so much of his life overlooked the area of the town called Fishwick Bottoms (locally as known as the “Loney” or the “ Bonk”) and from its land you could look down to the distant River Ribble. For anyone who knows the area the house (I suppose it might have been called a smallholding, although it wasn’t farmed in my lifetime) had a considerable area of land around it containing barns and greenhouses and the like. It stood at the point behind what used to be Fishwick Secondary Modern School (which I attended in the mid 1950s) where Church Avenue bends round to became Neston Street. In the distant past the house must have been very much at the edge of Preston - almost in the "countryside" I guess - but as the Callon Estate, Fishwick School and other surrounding areas were built and the Preston urban area spread in the 1920s and 30s it became part of that urbanisation. From the side door which was on Church Avenue and always used (never the front door!) one could see the nearby St Teresa’s Roman Catholic Church. Strangely, the actual house address was 9 Manning Road since the front door was actually on the unmade track that was, at that time, the continuation of Manning Road just off New Hall Lane. I presume that when the Fishwick School playing fields where put down in the late 1930’s the effect was to cut Manning Road into two – one end at New Hall Lane and the other at the end of Church Avenue. When I made a visit a few years ago I realised that the unmade track that was Manning Road in my childhood and before has been made into a proper street with houses and has been renamed and terminates as Church Avenue.

|

John (standing) and his older brother Joe, my

granddad, in about 1908

|

The house

had been in the family for a long time and for John’s father (James, my great

grandfather who died many years before I was born) it was his place of work as

a blacksmith and iron moulder. James Derbyshire and his wife Jane (née Fisher) had originally come from the Bolton-le-Sands area near Morecambe Bay and moved to Preston sometime at the turn of the century but by 1915 they were established in the house in Preston with three children: Joe (my grandfather, born in the Bolton le Sands area in the early 1891), Annie (who became Annie Nicholson and lived in Garstang) and John, born in 1897. At the side of the house was James' workshop a

large, earth floored shed filled with ancient iron tools, workbenches, a

forge and a vast selection of horse tack - old saddles, huge numbers of rusting horseshoes, bridles and other items I could not name; as a child I can remember playing in this wonderland! Here in Nottingham

in my porch I still have a cast iron door stop moulded into the shape of a lion

made by my great grandfather probably in the early years of the 20th

century – it’s a nice little link with my past. But if the smithy was a

wonderland so, too, were the surrounding grounds of the house. My friends Jack

Greenhalgh and Jimmy Kellett (who both lived nearby) and I played hide and

seek, soldiers, cowboys & indians and a thousand other boyish games for hours in the old

tumbledown barns and greenhouses. One

day I vividly remember we all three chased a huge rat that we saw near a barn.

The animal disappeared into the barn but our bravery stopped there – although

we threw stones into the barn none of us were brave enough to venture inside.

Presumably by then the creature was down in its lair – but we weren’t prepared

to find out! On another occasion we were playing hide and seek and I decided to

stand on top of an old oil barrel to look for my pals. Unfortunately the barrel

was riddled with rust and I fell straight through gashing my thigh badly; my

great grandma had to bandage me up with a piece of old shirt that she tore into strips. The scar is still there today, almost 70 years later; I suppose in this day and age I would have been whizzed off to A&E with flashing blue lights but we were made of sterner stuff in those days so a few strips of one of my Uncle John's old shirts had to do!

I have many

happy memories, too, of the house. It was a large detached house but the

kitchen and the attached outhouse were the only rooms ever really used. The

rest of the house always seemed to me to be an unused, bleak affair filled with

an ancient grandfather clock, great Victorian sideboards and other old furniture and faded carpets. I remember, too,

that the rest of the house always seemed unlived in and cold - fires were never

lit there, curtains left drawn so that the rooms were gloomy and many of the pieces of furniture were covered with dust sheets.

The outhouse, which adjoined the kitchen, and through which every visitor came

to get into the house (I don’t think that the front door of the house had been

opened in years!) had a lavatory and several old tables usually filled with

windfall apples, bowls of eggs from the few hens that were kept, or various

vegetables that were in season and had been grown in the largely overgrown garden. There was a huge old stone sink, a dolly tub, and a selection of aging kitchen implements and apparatus – especially an old mangle

which, as a child I loved to test my strength against by turning the huge wooden rollers. On rainy days my great grandmother would hang

her washing up on the wooden airing rack which was suspended from the outhouse

ceiling.

From the

pungent smell of windfall apples and damp washing in the outhouse one stepped

into the kitchen – the house proper - with its huge black shiny kitchen range

and roaring fire, always warm and

welcoming whatever the weather. Although there was an old, working gas cooker in the outhouse, the soot

blackened kettle was always boiled on the fire and my great grandmother seemed to cook everything in the oven at the side of the fire.

As a young child I was often taken to visit “Grandma and Uncle John” on a Saturday evening; we would walk up New Hall Lane from Caroline Street where we lived and I would sit - being seen and not heard - on the ancient, hard and very lumpy chez lounge near the kitchen range and the fire while the adults talked and my very old (to my young eyes) grandmother sat in her rocking chair. Then, just before we left, she would open the range oven door and pull out a steaming bowl of rice pudding left over from lunchtime. This would be presented to me with a spoon and she would say “I’ve saved you the toffee (the thick skin of the pudding) – it’s the best bit, eat it up Tony it's good for you". And I always did – although I’m not a pudding lover, I’ve loved the “toffee” on a rice pudding ever since!

Then, at about nine o'clock, as we set off for home; Uncle John would appear dressed smartly in his old fashioned brown suit complete with waistcoat and gold watch chain, don his trilby, and he would walk with us down Church Avenue to where it joined New Hall Lane. We would carry on down the Lane bound for Caroline Street but he would disappear into the Hesketh Arms pub for his Saturday night half of mild. I know that John would go for his “quiet half” most evenings – sometimes to the Hesketh Arms, other nights further afield – especially the Bull & Royal in the middle of Preston.

As a young child I was often taken to visit “Grandma and Uncle John” on a Saturday evening; we would walk up New Hall Lane from Caroline Street where we lived and I would sit - being seen and not heard - on the ancient, hard and very lumpy chez lounge near the kitchen range and the fire while the adults talked and my very old (to my young eyes) grandmother sat in her rocking chair. Then, just before we left, she would open the range oven door and pull out a steaming bowl of rice pudding left over from lunchtime. This would be presented to me with a spoon and she would say “I’ve saved you the toffee (the thick skin of the pudding) – it’s the best bit, eat it up Tony it's good for you". And I always did – although I’m not a pudding lover, I’ve loved the “toffee” on a rice pudding ever since!

|

Me with my great grandmother at the house

in Church Avenue. This would be in about 1946.

St Teresa's church is in the background

|

Then, at about nine o'clock, as we set off for home; Uncle John would appear dressed smartly in his old fashioned brown suit complete with waistcoat and gold watch chain, don his trilby, and he would walk with us down Church Avenue to where it joined New Hall Lane. We would carry on down the Lane bound for Caroline Street but he would disappear into the Hesketh Arms pub for his Saturday night half of mild. I know that John would go for his “quiet half” most evenings – sometimes to the Hesketh Arms, other nights further afield – especially the Bull & Royal in the middle of Preston.

When my

great grandmother died in the mid fifties John moved to the little

wooden bungalow that he had bought in Cabus, nearer to the Garstang Creamery where

he had worked for many years. The bungalow was tiny and called "Woodlands" and was more or less opposite Dicky Dunn's Transport Café - more commonly referred to in those days as "Dirty Dick's"! "Woodlands", I think, is long gone now but it was just along the A6 road from what was the Mayfield Café. Mayfield, when I used to visit my great aunt Annie as a child in the late 1940s & early 50s was a bungalow and had been first owned by Annie, John's sister, who was married to Bill Nicholson. Bill and Annie lived and farmed in the Garstang area throughout their married lives. The original Mayfield bungalow had been planned and largely built by John and Annie's elder brother Joe (my grandfather) who earned his living in property repair and building. Annie & Bill started a business at Mayfield - a café - on the A6, I assume that they thought that as car travel was becoming increasingly common in those 1930/1940s days this was a good business plan - it clearly worked and they soon had to extend the place. From serving teas in the bungalow they had a dining/tea room built. I can remember making frequent visits there in the 1950s with my

parents and each time gazing at an old black and white framed photograph

that hung on the wall. It showed my auntie Annie standing smiling in the café

and sitting at a table complete with table cloth and cutlery King George V and

Queen Mary each with a cup of tea in front of them. As I gazed at the

photograph auntie Annie would again tell the story (as she did each time I

visited!) of how the King and Queen were visiting Lancashire and travelling

north. They had stopped at Mayfield for “refreshments” – my auntie had been

warned the day before that this would occur and that the café must be closed so

that His Majesty could enjoy his afternoon tea uninterrupted! Over the years it was further extended and became a well known and used transport café in the 50s and 60s. Today it is "Crofters" a large, gross and graceless looking "hotel & tavern" - whatever that might be - where casino nights, late night discos and other such dubious events

take place – a far cry from King George V & Queen Mary! When Annie & Billy gave up Mayfield in the early 1950s they moved just a few hundred yards along the A6 nearer to what then was the Burlingham Caravans site. They had a large detached, bay windowed, house built, set back from the road and called their new home "Daybreak" which we often visited and seemed to my eyes very grand - the last time I drove past some years ago the house still stood there, much as I remember it from my childhood.

|

Mayfield in its original form - it later had an extension as it

became a café - later a transport café and now Crofters

|

I never revisited John's old house in Preston and left the area to live in Nottingham in the mid sixties. When I did return a few years ago I decided to make a nostalgic trip around the places of my childhood and I discovered that my great grandmother’s house was no more – instead there stood several well established houses bungalows. They had obviously been there for some considerable time, all evidence of the past use of the land gone forever.

But as I stood there looking at the modern houses and bungalows now sited on the place where my great grandparents and great uncle had lived and worked for most of their lives, and where I had enjoyed many happy childhood hours, I wondered if anyone knew of the old house that had stood there half a century before. And I wondered if anyone had an inkling of a bit of history that had occurred there when, in a tiny way, my family’s history became part of the nation’s – a small, perhaps, insignificant event but one which ultimately had a huge impact upon my own life and that of one of my children.

|

My great grandmother Jane Derbyshire, shortly

before she died in the early 50s.

She is being presented with a bouquet as

the oldest pensioner in

Preston at the time.

|

You see, I mentioned at the top of these ramblings that I loved Uncle John and much of my “hero worship” and respect for him was because of something that I knew of him: he had run away to war when he was still a youngster! His older brother Joe had enlisted and John, several years younger and still only 17, broke all the rules and without permission "took the King's shilling" and joined up. I can remember my great grandmother sitting in her rocking chair in the kitchen in the old house and telling me, shortly before she died, that she had no idea where her younger son John had gone – except that he had gone off to war.

It was 1915. John’s older brother – Joe – my granddad had signed up for the Loyal North Lancs Regiment in December (see my blogs: Touching the Past and A Little Bit of Preston Deep in a Foreign Field) and a few weeks later young John just disappeared – gone off to war. In those days many people didn’t have birth certificates so it was easy for someone to join up and lie about their age. The minimum age for joining up was 18 and for armed service overseas it was 19. John was just over 17½. Within weeks, however, he was in France, his mother and father desperately worried. Depending upon how you look at it he was lucky. It is estimated that about 250,000 boys served in France during the Great War – John was one of them. Until mid-way through 1916 the British army was largely volunteers (like my granddad) – men who answered the call. The army was desperate for men so they didn’t ask too many questions when someone like my great uncle turned up at the enlistment office. In 1916, however, the rules changed; conscription was introduced so suddenly there were a lot more men available for the army to draw upon and thus, the need to take on anybody and everybody lessened and the number of underage recruits slowly dried up. John must have been one of the last to be recruited in such a way.

At last, in late September 1916, word came to James and Jane in Preston that he was in hospital in London and his brother Joe, who happened to be on leave at the time, was sent off to the capital to find his younger brother. I can still remember both my grandfather and great uncle relating the story of how Joe searched the London hospitals for his injured brother. It was a huge problem; the hospitals were full to overflowing, administration and details about patients was scarce and, worst of all, John had his face bandaged up so was not easily recognisable. Eventually, however, he was found and some time later returned to Preston, his war service as a combatant effectively over. He wasn’t officially discharged until the end of the hostilities but spent the rest of the war in England in non-combative duties. I do know that he received a severe reprimand from his mother and father – and I’ve often idly tried to imagine the scene in that little kitchen with the roaring fire and the shiny kitchen range as the young John, his eye heavily bandaged came through the door. I’ve often wondered, too, if that event was perhaps a factor in John never marrying but living with his parents and then his widowed mother for the rest of their lives. I’ll never know, but the story both excited and intrigued me. To me, as a child, this was the stuff of dreams and high adventure and it gave this quiet, gentle, elderly man an air of mystery and excitement! This was further regularly heightened when, whenever we went to visit him he would take out what he called his “war souvenir” - his glass eye - and lay it on the mantelpiece! It was his party trick which always ensured gasps of horror or delight but thrilled me and made Uncle John very special.

He had only a very ordinary job – working at Garstang Creamery where, amongst other dairy products, Lancashire Cheese was made - but as I grew

into my teenage years it increasingly

became obvious to me that he had much more to him. He was well read and seemed to

have important things to say; to my youthful mind he "knew stuff”. As I grew up I

can remember having increasingly serious conversations with him about events in the news. He was, I realised, both articulate and understanding, able to talk knowledgeably, it seemed to me, about anything; to my teenage eyes he was undoubtedly "on the ball". Each night he would

listen to the Home Service nine o'clock news on the radio – an old crackly machine that

looked as if it came from the Great War trenches! - and he would always comment on what he heard, saying things which to my young ears were very clever, thoughtful and wise. And, having listened to the news he would put on his brown trilby

hat which matched his suit and with his watch chain across his waistcoat very

smartly walk down to the Hesketh Arms on New Hall Lane or perhaps into Preston to

have his nightly half pint of mild ale.

As the years passed he became a firm friend and in the last year or two before I went off to teacher training college I would enjoy sharing a beer with him and my dad each Saturday night. My dad would pick John up at his Cabus bungalow and they would pop out for their “quiet halves" of beer – usually to the Patten Arms at Winmarleigh but occasionally to the Royal Oak in Garstang or perhaps further afield to Morecambe or Lancaster and I would often go with them. We would sit there, a nineteen year old and a seventy year old enjoying each other’s company. Even though the years separated us we could always “connect”. Despite his bald head and advanced years he seemed to me to be a modern man and still young at heart with the capacity to talk to you and not at you. I can remember talking to him in the weeks following the Kennedy assassination and although by then he was in his late sixties I was thrilled that he wanted to know what I, a mere teenager, thought about that dreadful and - to those of my age and who lived through it - never to be forgotten event. "It's your world now, Tony" he said to me one Saturday night following the Dallas assassination of Kennedy "my generation have done our bit to make the world right so it's up to your generation to try now" - how thrilling is that when you're a teenager, a kind of passing of the generational torch, guaranteed to inspire and make you feel good - and for me at least, it was a coming of age thing which without any shadow of doubt gave my life some sort of meaning and goal. When I talked to him he always listened intently and responded – not always agreeing, but picking up the nuances and wanting to explore and think about what I thought and said - and in doing that it seemed to me (and still does) that he was implicitly recognising my opinions as worthy of consideration. He once asked me - and he was genuinely interested - as we sipped our beer “Now come on Tony tell me about these Rolling Stones (this was in the early 60s!) why do you youngsters like them?” I can remember him talking of the first great Liverpool football team created by Bill Shankley as they succeeded in Europe and telling me “that’s the way that football is going to be played from now on, like a chess match – none of this kick and rush stuff that we've been used to”. To me, as a teenager, used to my parents and older people putting teenagers down this was music to my young ears. And I still vividly remember, when I was about to go off to college and (much to my mother’s disapproval) I had opened a bank account complete with cheque book (an unknown item in my family in those days). He spoke up for me when my mother expressed her strong disapproval – bank accounts and cheque books weren’t for “folk like us” she argued . “Now, Doris”, he said “I’ve been reading in the Daily Express that in a few years time we will all be paying for things with little plastic cards. Tony’s a young man now he has to be modern and move with the world”. I can still hear him saying those words and my mother huffing and puffing while I quietly raised my eyes to heaven and silently whispered a quiet “Thank you, God”! Paying with plastic cards! – I wonder if even Uncle John could have comprehended how the world would change? No, my great uncle John seemed to me at the time – and still does - to have had his finger on the pulse, to have thought things out and was his own man. As a callow teenager all those years ago, to me he was worldly wise, ahead of his time – to coin a modern phrase a “cool dude”!

American poet and author Maya Angelou once wrote: "I've learned that people will forget what you did and that people will forget what you said. But people will never forget how you made them feel" - that expresses exactly what I felt about uncle John, both all those years ago and still today. It is a gift given to few but he had it by the shed load - the ability to make people feel valued and good about themselves. Now, today, I am older than John was when he died, but his impact is as strong as ever - rarely a day goes by when I don't at some point think, "What would uncle John think, what would he do, what would he say?" .And, as a I ask myself this, from somewhere deep inside me I hear his long gone voice and somehow get the answer that I am seeking.

The boy who

ran off to war remained a young man at heart up until he died in 1974 and I have often reflected that it was through him that I

learned much about growing up and being an adult. He wasn’t loud or brash or talkative – indeed,

if we sat in the pub, him enjoying his half pint, he would usually say little, but

what came out was always quietly said and worth listening to.

He had no agenda and just quietly got on with the life that fate had

dealt him. I have no idea why he never married but lived with his mother until

she died but whatever the reason for his bachelorhood he was a lovely

and much loved man. Although quiet, retiring and undemonstrative his love

was unconditional. He was what you saw and you learned not only from what he

said but from what he did and how he behaved. He had a quiet and gentle authority and I loved and respected

him not because he demanded it but because of who and

what he was - and especially because of the obvious value that he placed upon me and my young beliefs

and feelings. He listened, and such advice as he might have wanted to

impart to me he did without expectation or insistence. I don’t know whether he saw

himself as older and therefore wiser (although he clearly was) but he never

thrust that experience down my throat. Whatever experiences and wisdom he

had gleaned from his life was passed on without it being a lesson or a homily and I soaked up his wisdom like a sponge – he was the supreme teacher - but never knew it.

|

John as I always remember him.

No airs and graces - just a gentle

decent man who had lived a good

and worthy life. But to me, a

man ahead of his time and with a story to tell. |

Uncle John died in April 1974 and when my own son was born a few months later in September 1974 there was only ever going to be one name for him – John. And even today, all these years after my great uncle’s death I still think of him and those quiet conversations and half pints of mild ale that we shared in the Patten Arms at Winmarleigh - a teenager and a pensioner, separated by half a century in age but by a much bigger gulf in life experiences and expectations. He was a child of Victorian England and had witnessed the horrors of the trenches first hand at the same age as I was when we sat together in the pub. Whereas I was a child of Attlee's "New Jerusalem" and the Beatles' "Swinging Sixties", comfortable, confident, with the whole world at my feet he had been born into generation who suffered huge hardships, wars and want that people like me could not begin to comprehend. As I sat next to him in the pub and still today, I imagine him as a young boy running off to war, a boy amongst men, involved in the horror and the blood of the trenches – a thing which both terrifies me and humbles me - but which he just took in his stride – never boasting of his involvement or complaining about the injury that changed his life. Like others of his generation he just got on with things. Sometimes it seems a far cry from today when so many appear to wear their hearts on their sleeves and want to shout from the rooftops of their disadvantage and problems, or vent their spleen against life, society and its unfairness. I'm sure that John had many things that in the quietness of his own mind he could have complained about - the hardships of his life: two world wars, a great depression, never married, never had his own family, the terrible impact of the Great War upon him, perhaps broken dreams and ambitions, great sadnesses and all the other things that go into the lives of all of us. But I never heard him once complain – he simply got on with it. Maybe there's a lesson for all of us in that fact.

Uncle John was an honourable, brave, decent, courteous gentle and generous man. One can, I think, give no higher praise of any person whatever their background, calling, profession or standing in the world than to say he was a good man and lived a good life; John Derbyshire was such a person. He could not, I believe, have had any inkling that he would have such a profound and lasting effect upon and importance to me - and indeed still does. I don't know how he would have reacted to that but I suspect that he would probably have just smiled, nodded and looked into his beer glass and quietly and gently said, without looking up, “Aye , good - well that’s alright then”. But I'd also like to think that deep down he would have gained some quiet satisfaction that although he had no family or children of his own he had made such an impression on me and my life and ultimately my family and that his name and memory lives on in my son, his great, great nephew.