|

| Alan Johnson - wannabe rock guitarist, postman, trades union official, MP, Home Secretary and elder statesman - and chronicler of the late 20th century |

As I have become older biographies and autobiographies have increasingly become my most enjoyed read and amongst my favourites are:

- The Outcasts’ Outcast – a wonderful biography of Lord Longford by Peter Stanford. The life of the great reforming Lord – a man of infinite goodness and intention who was often reviled by the media and much of the population

- Eric Clapton – The Autobiography. The life of the great rock

guitarist

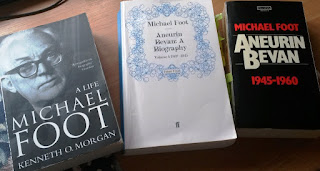

- Michael Foot by Kenneth O. Morgan – the life of the great Labour politician and probably the last of the great political orators

- Macmillan by Alistair Horne. The biography of probably the last ‘one nation’ Tory Prime Minister. Famed for his phrase “You’ve never had it so good” he was one of the few more recent Prime Ministers that we could describe as a statesman.

- The Time of my Life – the autobiography of Dennis Healey, often described as the best Prime Minister England never had.

- Lincoln by Carl Sandburg – a truly inspiring trilogy about a truly inspiring President

- Kennedy - An Unfinished Life by Robert Dallek. One of the best of the many biographies of the iconic President

- Trautmann – the biography of the much loved German goalkeeper by Alan Rowlands

- Harold Larwood by Duncan Hamilton – the biography of the great fast bowler forever remembered for his part in the Bodyline Test Series.

- Tom Finney – My Autobiography. The story of arguably England’s greatest footballer who was born and lived only a few streets away from where I grew up and who I watched play so many times.

- The Long Walk to Freedom – Nelson Mandella’s life and times

- My Life in Pieces – the wonderful story of the great actor Simon Callow

- Testament of Youth – not strictly a biography but the great tale and indictment of war by Vera Brittain

- Roosevelt by Conrad Black – the life of the great American President

- Boycott, the Autobiography – the life and career of the great English batsman Geoffrey Boycott

- Aneurin Bevan the biography of the great Welsh Labour MP, father of the NHS and great orator by his protégé Michael Foot.

|

| Three sporting greats |

And, I suppose that is true of virtually all the biographies

that I have listed. Each person written about in their way ‘made a difference’ – be it on the sports

field, in politics, in music or in life. The two music biographies that I have

mentioned – that of rock guitarist Eric Clapton and that of the Baroque

composer Bach would seem on the surface to be miles apart but in their age and

beyond both changed the musical world. So, too, with political biographies such

as those of Harold Macmillan and Aneuurin Bevan. Macmillan, the public school

boy, like Lord Longford, had the world at his feet. It was almost predictable

from the day of his birth that he would achieve high office. And at the other

end of the spectrum, Bevan from the most humble of backgrounds who worked from

the very bottom to the top. Politically and socially these two were worlds

apart. Macmillan, a Conservative by both upbringing and inclination would have

sat in the House of Commons and heard

the fiery and heart on sleeve Bevan scathingly

castigate Macmillan’s Prime Ministerial predecessor thus: “Sir Anthony Eden has been pretending that he is now invading Egypt in order to strengthen the United Nations. Every burglar of course could say the same thing, he could argue that he was entering the house in order to train the police. So, if Sir Anthony Eden is sincere in what he is saying, and he may be, he may be, then if he is sincere in what he is saying then he is too stupid to be a prime minister.” Macmillan would undoubtedly have winced but at the same time had a worthy riposte to Bevan when in 1948 the Welshman declared “No amount of cajolery, and no attempts at ethical or social seduction,

can eradicate from my heart a deep burning hatred for the Tory Party. So far as

I am concerned they are lower than vermin.” And for his part Bevan would have been

infuriated by the unflappable, incisive and pragmatic Macmillan when he calmly

declared “It is the duty of HM Government

neither to flap or falter” or when

‘Supermac’ as he was labelled suggested that the population ‘had never had it so good’ or finally

when asked what things in politics he most feared he allegedly and laconically replied ‘Events dear boy, events’. But, as with Clapton and Bach, as with

Longford and Trautmann, as with Larwood and Lincoln and all the rest, Macmillan and Bevan were game changers

and their biographies illustrate this.

The life stories that I have enjoyed most are those which

have, in some way, resonated with me as an individual and reflected my own experience or convictions – my

childhood, my background, my basic beliefs about life. Or, often I have enjoyed

them because the subject is someone for whom I have a great admiration – although

not necessarily liked. Sometimes the personal link is obvious – for example the

biography of Tom Finney tells of the streets, people and places that I knew as

I grew up, like him in Preston. As I read it I can picture every place and

event as well as appreciate the life story of this great footballer. Similarly,

the life of Nye Bevan chimed with me partly because of his humble background

but especially because his beliefs, his idealism, his commitment and because his

passionate words expressed my ill thought out feelings more or less exactly.

Other biographies have spoken to me in other ways – especially in that they might

have opened up an understanding of a person that was not there previously; those of Macmillan and Eric Clapton very definitely fall into that category. In the

“admiration” bracket I would include the biographies the great actor Simon

Callow, the writer Doris Lessing, the economist John Maynard Keynes and the

life stories of Michael Foot and Dennis Healey – the latter two being men who often crossed

political swords although of the same political creed but for whom I hold a

great respect and admiration. Occasionally I read something which disappoints

or frustrates me – and a previous admiration begins to wane. For example, I

have always had a huge respect and admiration for politician Shirley Williams,

the daughter of the great pacifist Vera Brittain. Brittain’s great work Testament of Youth is, I believe, one of

the great books and should be compulsory reading in all schools and I long felt

that her daughter, Shirley Williams, lived many of her mother’s ideals and beliefs

as a Labour politician – especially when she was Minister for Education. As a

teacher I had great respect for her and much of that respect is still there –

she was and still is, in my view, the last great Minister for Education that we had. But,

having said, that I found her autobiography (Climbing the Bookshelves) disappointing and shallow. After reading

it I began to seriously question her real commitment and passion and felt let

down wondering if she really believed in anything at all. Deep down, it seemed

to me, she had all the ideals that I cherished but never the will and the

passion to turn these into reality. Politics, I think, is a brutal game and it

seemed increasingly that Shirley Williams was born into a privileged background

but unlike Lord Longford (and to use sporting parlance) she talked a good game

but never really got bloodied. Maybe I’m wrong! Sometimes I have enjoyed books which might not

be strictly biographies but are written by people who have lived through great

events and use these, and their life story, to provide an insight into world history

and society. Two writers stand out here: historian Eric Hobsbawm with his Interesting Times and Fractured Times and, secondly, the

writings of historian and political scientist, the late Tony Judt – especially Ill Fares the Land and The Memory Chalet and Postwar: A History of

Europe Since 1945. Ill Fares the Land

and The Memory Chalet are two

books which have left a lasting impression and if forced to choose would certainly take these to support me should I be cast onto a desert island! And

finally, it is always a joy to read of someone who I don’t have any particular

affection for – or maybe even dislike – and to then find that despite my

prejudices that the subject does have redeeming features. The biography of

impeached and disgraced American President Richard Nixon by Conrad Black

springs to mind here; despite Nixon’s politics and the manner of his downfall

via the Watergate scandal, “Tricky Dickie” (as he was often called at the time),

was maybe not so bad as often painted. Like others I have mentioned, he came

from humble origins, rose to the supreme office, was the ultimate "fixer" politician and on balance made a lasting

contribution to the world - especially in opening up dialogue between the

communist and the free world. Following this line of thought I keep trying to

convince myself that I should read the biography of Margaret Thatcher! I’m sure

that I will find some things to applaud. I certainly respected and admired her

– there can be little doubt that her commitment, single mindedness and industry

changed Britain and probably the world for ever. But, I fear that my dislike, indeed hatred and

revulsion of her policies, style, manner and arrogance would lead me to, at the

very least, hurl the book through the window or more likely cause my sudden

demise via a combination of apoplectic fit and heart attack. Perhaps she is one

biography too far.

|

| Tricky - "there will be no whitewash at the White House" - Dickie Richard Nixon". There was, but maybe he wasn't all bad. |

At the top of this blog I mentioned the biography which I am

currently reading – indeed have just, last night, finished – the second

instalment of Labour politician and now elder statesman, Alan Johnson’s

memoirs. Aptly named Please Mister

Postman (Johnson spent much of his pre-MP life working in the postal service) the memoir, and it’s first

instalment This Boy, ticks all the

biographical boxes for me. This Boy

when it was published a couple of years ago was widely acclaimed and rightly became

an immediate best seller; it told the tale of Johnson’s very humble, and at

times desperate, upbringing in post war London against the backdrop of the 50s

and early 60s. Apart being beautifully written and inspiring as Johnson and his

older sister struggled to overcome the heavily stacked odds it is also a

wonderfully evocative and accurate memoir of the time and place. I could relate

to it exactly and the convictions about life, society and politics that were

slowly dawning in Johnson’s young mind I could largely recognise as similar to my own.

When he mentioned that one of his favourite books was the western Shane it rang an immediate bell – one of

my all time favourite films is Shane (see

blog: Wooden Ships and Iron Men -July

2011) and as I read of his early teenage years I often felt as if I was reading

my own story. And this feeling has continued into the second instalment Please Mister Postman when Johnson

traces his marriage, setting up home in the late 60s, his growing interest in

reading and in his dawning political awareness, aspirations and ambitions. He

talks of his “secret” reading of The

Times when all his work colleagues read the tabloid newspapers – I can

relate exactly to that; my wife often says that when we were at college – and

before we were an “item” - she always

noticed me as I would always have my copy of The Guardian with me! He talks of learning new phrases such as lingua franca as his work brings him into contact with a wider range of people and situations. When I read that I reflected how many times that sort of thing happened to me when I went to college and was suddenly mixing with fellow students who had come from very different social backgrounds to my own. I still remember vividly the very first night at college when a formal dinner was held and I found myself sitting on a table with a lecturer and seven other students; I had never sat at a table where there was a range of cutlery set out in front of me or where grace would be said or wine served. I sat praying that I would not commit a social sin and watched everyone of the others like a hawk to see which knife, fork or spoon they used, how they held them how often they sipped their wine, how they passed the salt and pepper, what phrases they used, how they laughed, when they laughed. I was on a steep learning curve and as I read Johnson's memoir I sensed the same thing had happened to him too. I can relate, too, to the pictures he draws

of life in the 70s – the cheap white (often German) wine like Blue Nun, the

Party Seven [pint] beer cans which were popular at the time, the slowly growing

chance for ordinary people to own things like cars and telephones. Then came

the growing tensions that began to appear within society: the Labour Party

becoming dominated for a time by left wing militants, the miners’ strike, the

Thatcher government and so on. Johnson documents these all too well and his

words took me back to that time with a

vengeance.

And by a stroke of pure coincidence I was engrossed with

Johnson’s depiction of where he and his wife settled in the Thames Valley town

of Slough. This became very personal for me since my son, when he moved to that

area over 15 years ago, shared a house with a friend only a couple of roads

away from where Johnson had lived on the Britwell Estate. My son then bought a

flat in the area where each day Johnson would have delivered his letters all

those years before. As with Johnson’s first book depicting his childhood I

began to feel that I was almost part of this story! I knew the pubs he mentions: The Feathers opposite the gates to the

great Cliveden House (see blog: A Saturday Afternoon Walk Through History - May 2012) and the Jolly Woodman near to Dorneywood – both places where we have enjoyed

a drink and meals – and many of the other areas and places Johnson writes of. Today my son still

lives in the Thames Valley and I know that when I next visit him and his family

I will be noticing, with new interest and insight, some of the places that

Johnson referred to.

And finally, Johnson’s occasional comments that he makes

concerning his political beliefs and ambitions they too resonated. He talks of

the schools of the time although called comprehensives were that in name only

for selection still existed and “the best” were creamed off to go to the local

grammar school, When I started teaching that was exactly the same situation

that we had here in Nottinghamshire. In my village, children I taught took the

11+ test and if they “passed” then they went to one of the two comprehensives

in neighbouring West Bridgford; if they “failed” then they were sent to the

local village secondary modern. And yet, when I moved schools to teach in West

Bridgford I discovered that children living there did not need to take the 11+

at all to go to these same “comprehensives” - they simply transferred to the one

of their choice. So children within only a couple of miles of each other were

treated completely differently – and I would argue grossly unfairly. It was,

too, a situation that had an interesting and telling spin off. The parents in

my village whose children had to take the 11+ viewed the comprehensives as

highly desirable, a step up, and their ultimate goal and where their child, if

they passed the 11+ would gain opportunities unheard of at the local village

secondary modern. Like a rare antiques these schools were highly valued because

they appeared exclusive. But the West Bridgford parents on the other hand had a

low opinion of the comprehensives – after all any child living in West Bridgford

could go there so there was no exclusivity. For the West Bridgford parent it was a case of familiarity

breeding contempt. In fact, of course, as with Johnson’s example in Slough, the

whole situation made a nonsense of the term “comprehensive”; for some children

(the “less able” as defined by the test my village) were being hived off to a

secondary modern whilst at the other end “bright” children were gaining

admittance to selective schools in wider Nottingham. These “comprehensives”

were not comprehensive at all! It was a sham reinforced by parental snobbery

and ambition and it went on for several years before some limited kind of

equality was put in place. It would be nice to think that anachronisms like

this are a thing of the past; sadly they are not, inequality and educational

snobbery are alive and well in 21st century Britain. In Trafford

(Manchester) for example, where my granddaughters are at school, and where selection grotesquely skews the school system and thwarts any real chance of equality. It is an undeniable truth that England

has never, at any time in its history, had an education “system” – for “system”

implies something thought out, coordinated, logical, organised in a progressive manner, whole and cohesive. Instead, we have always had and still

have a lottery, an ill un-thought out, disorganised and fractured hotchpotch of competing interests and self interest

that creaks along with no discernible logical or educational structure giving some huge advantages and others almost insurmountable disadvantages.

In the 21st century as yet more pieces of nonsense - free schools and academies - are introduced into this complex

and unedifying mess of independent schools, public

schools, faith schools, grammar school, comprehensives, aided, voluntary aided, controlled schools, voluntary

controlled schools........and so on – equality via education becomes more and

more unlikely as they all vie for a bit of the educational action. Whatever the merits of the various kinds of school that we have in this country what we have could not even in the broadest of terms by called a "system". If some future dictator or visitor from Mars decided to impose an education system on the UK then this is exactly what he or she would not have - it is a mess and a shambles. It is a great sadness and source of no little anger to me that after all

these years the Labour Party have never been prepared to grasp the nettle and

resolve this situation once and for all.

That, however, is another story! There were other things

that resonated in Johnson’s memoir such as the left wing “take over” of the

Labour Party. Like Johnson, I remember that as a very difficult time. In

schools we were increasingly being subjected to what I considered to be left

wing propaganda at in-service courses and from the local education authority. Political correctness ran amok and for a time

one feared that Orwell’s dystopian society really had arrived. It was the only time in my almost 60 years of

reading The Guardian that I gave the

newspaper up for a few months in favour of The

Times. I remember too, as Johnson refers to, the coming of Neil Kinnock –

now often, and wrongly, criticised by

“New” Labour. But Kinnock began the slow rebuilding of the Party after the left

wing debacle and in my view put the building blocks in place for Tony Blair’s later

victories.

And finally, I felt totally at home when I read towards

the end of the book of Johnson’s admiration for Michael Foot and especially

Foot’s magnificent biography of Nye Bevan which I listed above as one of my

favourite biographies. Foot and Bevan may, in the modern Labour Party, be “old

hat”, and not the subject of polite conversation amongst the Party apparatchiks and the trendy young turks, indistinguishable

from their Tory counterparts and those who are

currently vying for the leadership of the Party following the election result a

few weeks ago. But when I read of Johnson’s respect for these two giants of

another age I felt that maybe all is not lost!

When I read this reference to Foot and Bevan the circle was

completed, the icing on the cake; and as last night I closed the book having got to the

end I began to wonder if Johnson will write a third instalment and if so what

will it be called? His previous two have been the titles of Beatles’ songs: This Boy and Please Mister Postman reflecting, I suppose, Johnson’s unfulfilled

ambition from his teenage years of becoming a rock guitarist. So what will he

choose next as his memoirs come up to date and he becomes a cabinet minister

holding high office – Yesterday or maybe

All You Need Is Love or A day in the Life or We Can Work It Out or maybe it's just got to be Paperback Writer! I shall look out for

the next instalment if there is to be one – but until then there are plenty of

other biographies to go at; sitting on my desk at the moment are the biographies

of the late and much respected politician Roy Jenkins and the ex-Archbishop of

Canterbury, and a man I hugely admire - Rowan Williams. So there’s plenty to

keep me out of mischief!

No comments:

Post a Comment